When we look at a photo of an open refrigerator, are we inside or outside the refrigerator?

Historically, from the time when linear perspective was introduced, European artists in particular made it their task to establish a viewpoint for the viewer. This tradition has endured. In many public places you will see specific positions marked as ‘Viewing place’ or ‘Photography point’. A case in point is in the grounds of Laycock Abbey, once home to William Henry Fox Talbot[1], where at several places in the grounds there are frames, positioned in such a way as to suggest as an ‘ideal’ photograph of the landscape by defining a particular viewing point.

However, not all artists are comfortable with the degree of constraint that either a strict perspective or a single defined viewing angle imposes and chose to rebel. A more contemporary approach is to allow considerable freedom in the creation of a work. It is acceptable to ignore the suggested ideal and use the wider space to spark alternative interpretations and options so that both the composer and the viewer can liberate new ideas.

Tradition also determines that a composition is titled to aid the understanding and appreciation of the work. However, in many cases the author of the artwork is seen to bypass the expectation of the audience by simply choosing ‘Untitled’ for their work. This in itself is open to interpretation, it may be seen by some as lazy, others as arrogance and others again as leaving more space for the viewer’s imagination to build on the work.

Titles though, can serve several purposes. Titles may be given to aid cataloguing, to identify exactly which of the numerous variations of a particular artist’s work it is. Sadly, too often, titles of visual artworks are merely literal descriptions. A simple statement of the obvious, potentially belittling the viewer by questioning their ability to identify, easily and simply, what is in front of them. Literal descriptions can also constrain the interpretation by the viewer by reinforcing in words the immediately available image hence narrowly channelling thought and providing a mental straitjacket.

Another option is the careful selection of a title that is intended to add something to the work, such as a clue to the inspiration of the artist or a potential line of enquiry that could be followed by the viewer when contemplating it.

There was no pipe in the famous painting by René Magritte.[2] “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.”[3]

The French philosopher Michel Foucault[4] in his book The Order of Things analyses the relationship between language and visually perceived ‘reality’ with the example of a painting of Las Meninas[5] by Diego Velázquez.[6]

“… the relation of language to painting is an infinite relation. It is not that words are imperfect, or that, when confronted by the visible, they prove insuperably inadequate. Neither can be reduced to the other’s terms: it is in vain that we say what we see; what we see never resides in what we say. And it is in vain that we attempt to show, by the use of images, metaphors, or similes, what we are saying; the space where they achieve their splendour is not that deployed by our eyes but that defined by the sequential elements of syntax. …”

Foucault continues and suggests that naming depicted things can be merely an artifice.

“… it gives us a finger to point with, in other words, to pass surreptitiously from the space where one speaks, to the space where one looks; in other words, to fold one over the other as though they were equivalents. But if one wishes to keep the relation of language to vision open, if one wishes to treat their incompatibility as a starting-point for speech instead of as an obstacle to be avoided, so as to stay as close as possible to both, then one must erase those proper names and preserve the infinity of the task. It is perhaps through the medium of this grey, anonymous language, always over-meticulous and repetitive because too broad, that the painting may, little by little, release its illuminations.”[7]

Incidentally the title of the book in English is not a direct translation of the French title under which it was first published. It is however a direct translation of the title Foucault initially favoured when writing it. It is said that his editor influenced the choice of the French version.

So, returning to the photograph of the refrigerator; there are several possibilities, or for some maybe only one, to answer two questions with regards to the photograph of the open refrigerator – What is depicted? and Where are we standing?

Ceci n’est pas un réfrigérateur

Photography Point No. 3

Both depend on the perception of the viewer and that is shaped by their previous and current experiences. Is it a photograph of the refrigerator to be explored by an artist, engineer, marketeer, potential consumer or aficionado?

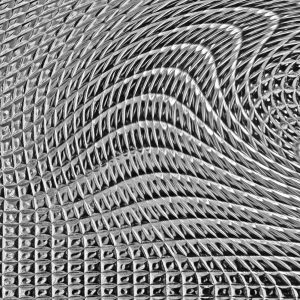

An artist may be perceiving the photograph only as material with its texture, size, tonal balance and disposition of the depicted elements. Alternatively, another may be using the photograph to explore some special characteristics of the depicted refrigerator with no interest in specifics and qualities of photography as a means of expression.

The major concern may be how well the photograph leverages the commercial possibilities of the item depicted or conversely, will the refrigerator meet the functional needs of me and my family?

There also is a possibility that the focus of interest is concerned neither with the refrigerator nor the photograph but with the way refrigerators have been depicted using various medias, is it indeed a refrigerator or an objet?

The number of possible conclusions can be numerous, depending on our standpoint. This is where a title can help or hinder tremendously.

So, where do we stand? Of course, we are neither outside nor inside of the refrigerator because there is no refrigerator.

“Ceci n’est pas un réfrigérateur.”

[1] William Henry Fox Talbot (11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877) was an English scientist, inventor and photography pioneer who invented a process he called calotype, essentially a precursor to photographic processes of the later 19th and 20th centuries.

[2] René François Ghislain Magritte (21 November 1898 – 15 August 1967) was a Belgian artist. His work is known for challenging observers’ preconditioned way of perception.

[3] The Treachery of Images (French: La Trahison des images) is a 1929 painting by Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte. It is also known as This Is Not a Pipe (French: Ceci n’est pas une pipe).

[4] Paul-Michel Foucault (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984) was a French philosopher.

[5] Las Meninas (English: Ladies-in-waiting) is a 1656 painting Diego Velázquez.

[6] Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599 – August 6, 1660) was a Spanish painter, the leading artist in the court of King Philip IV and of the Spanish Golden Age.

[7] The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (French: Les mots et les choses: Une archéologie des sciences humaines) Pg10, Paul-Michel Foucault, first published in 1966 éditions Gallimard. The quote is a fragment on analysis of the painting by Diego Velasquez, Las Meninas (1656). The chapter Las Meninas from this book is a pivotal text and a good suggestion for anybody trying to acquire understanding of the relationship between language and visually perceived ‘reality’.

Michel Foucault also wrote an essay Ceci n’est pas une pipe which was a contemplation on a painting by René Magritte, La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe).

Blue #011

Blue #005