I clearly remember the feeling of amazement when entering the Tate Modern in London for the first time, just after it opened to the public as a Contemporary Art Gallery in 2000. The Swiss architects, Herzog & De Meuron, succeeded in making visual the polarity of two vital compositional elements of architecture – space and construction. The contrast was created to such an extent that the 35 metre-high and 152 metre-long ‘vestibule’, the former turbine hall of the power station, made the generous exhibition spaces located on the side of this entrance look tiny and hardly sufficient to contain any significant number of artworks.

It was somewhat surprising for those visitors who were used to a dense distribution of exhibits in relation to the space available, but the grandness of the ’emptiness’ managed to silence any scepticism there may have been about the use of space. It was clear that the paradigm of the artwork/gallery/space/viewer relationship had been changed and embedded by acceptance at an institutional level.

The first impression clearly pointed to the emptiness of the space as an artwork in its own right. Besides that, there was an impression that the exhibits delicately ‘packed’ in large, opaque, protruding glass boxes on the sidewalls were meant to be perceived more as the symbols of Art than parts of interior exhibition spaces. This seemed so in tune with the contemporary time period and post-modernist mindset. The offer of the first artwork encountered being the vastness of space, to contemplate on or to lose oneself in, seemed a very progressive gesture from a newly opened art institution.[1]

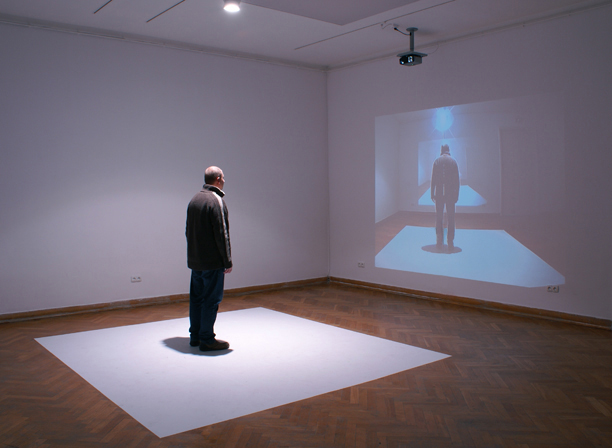

The space we most commonly imagine with regards to works of art is a gallery or environment for the exhibition, in which the works are arranged so viewers can stand in front of, or walk around, them. The traditional view is of a neutral space commandeered for the purpose of displaying the artefacts that are the centrepiece of the exhibition.

However, the reinterpretation of the exhibition space and challenges to the then traditional systems of the display, communication and perception had already been made a topic in modernist art practices. The division of space and artwork in modernism clearly stated the functions of each of these elements and the viewers knew where they stood, literally and figuratively, and where the boundaries of the artworks were. Viewers were also relatively at ease with their approach to the interpretation of the artwork, as modernist artwork was created to convert into language. It could be read. The syntax was given.

From a post-modernist point of view the space is not neutral, it is an active and integral element of the artwork. More often than not the artist’s idea is connected to the physical space available for the exhibition. Space is not only an element of display, it is also an important part of the creation and perception of an artwork.

The contemporary/post-modernist viewpoint, which is the basis of art philosophy of today, has lost the syntax entirely. Even if words exist they are not in the order we expect them to be. This means the viewer is not restricted as each has their own starting point, derived from their context, independent of the artwork. This fact provides an additional ‘space’ which becomes a crucial factor in the process of interpretation. The other element, due to the contemporary nature of the artwork, is the enhanced possibility of acquiring at least some knowledge of the context and triggers from which the artwork resulted. This further expands the space for interpretation.

The corollary of this is that it requires an effort as well as a desire to be able to get the most from contemporary artworks. This because they are neither created simply to be an entertainment nor as a decoration intended to fulfil any basic sensual expectations which give instant gratification. Art of today is rather an immersive experience, which requires the viewer to perform a process of analytical activity requiring proficiency in the tradition of artistic expression and philosophical thought. It is an intellectual engagement, both from the artist’s as well as the viewer’s position. The resulting emotion felt by viewers is thus personal, due to the space and effort they contribute, and the depth also dependent on their proficiency and application.

There is an oft-forgotten fact when encountering artworks from past times in a contemporary situation. We tend to forget that our perception and interpretation is unbreakably related to the present moment. Even the most believable historic recollections are not free from hypotheses and legends. We assume the historian was fully informed and that the narrative was correctly recorded or translated without accounting for any human error or bias. Remember that history is largely written by the victors, and art history is no different. Views dominant at any point in time prevail and that which is dominant often changes over time.

How an artwork is created and introduced to the viewer also undergoes significant transformations as the contemporary situation evolves. Perhaps the most significant transformation has been the emergence of the virtual space and ability to access it provided by the global growth and reach of the internet.

The once dominant situations where a viewer is physically standing in front of an art piece as if in front of a window, or when an experience is gained by walking around it, have become just two of many current methods of representation. That means the language of art has expanded and become richer. As the methods and systems of representation and ways of perception proliferate, literacy, the ability to read and interpret multiple elements of the language, has increased.

At the same time it has become impossible to define any ranking of superiority, putting one method over another. As the paradigm shifts new concepts are adopted which do not share common characteristics. That lack of commonality precludes direct comparisons.

There is also a departure from the assumption that an artwork is a material representation of the artist’s intention. The material form may not be present at all, instead of a tangible artefact we may be offered the possibility to replace it with an intangible space for mental activity. There are situations when the interpretation of an artwork becomes solely a work of intellectual self-expression. The link with the trigger, the original artwork under discussion, becomes broken and the interpretation becomes an artwork in its own right. Theoretically then, space can expand to infinity.

The separateness of artwork, context and viewer gradually ceases to exist. It becomes an entity that is constantly changing and repositioning itself towards a singularity where the exclusion of one part is not possible without destroying the totality of the work and comprehension not possible in a previous context.

The ambiguity of representation in the post-modern situation is increased even more by the fact that post-modernist artwork does not provide a clearly readable meaning. Instead there are numerous fragments of unknown context or even several contexts at once, which can be interpreted in variety of ways.

The effort required to do that, coupled with the interpretation being linked to the knowledge and experience of the viewer has led to accusations that contemporary art has become a restricted community and hence elitist. Some even assert that without an obvious meaning an artwork is meaningless. However, there is an alternative interpretation.

That each viewer contributes their own unique perspective to the experience of viewing, that the experience is constructed in their personal inner space, and without that the artwork is incomplete, means everyone can own a bespoke piece – what could be more egalitarian and further from elitism?

So, the fact that the artwork does not possess an obvious meaning does not indicate that it is meaningless, quite the reverse.

[1] The extension of Tate Modern (2016) has slightly diminished the conceptual purity of the space, but, at the same time, with its 64.5 m high tower and 60% more exhibition space, it has made it possible to encounter more art from the recent past.