Small sheets of paper covered with undistinguished pen strokes, strange shapes and undefinable forms. That is what a doodle can look like and more often than not the destination of these drawings is very likely to be the nearest wastepaper basket.

Let’s think about that though. Far from being simple they are often quite complex and illustrate an idea from deep in the subconscious. So there’s the irony, throwing them away is the waste.

What circumstances are conducive to doodle making? The precise triggers for this peculiar activity are far from clear, as some doodle prodigiously and some not at all. For those that do, it seems nothing much is required – just pen and paper nearby during an extended telephone conversation or lengthy lecture.

A doodle is described as the practice of drawing while the attention of the person is occupied with something else. If you are one of those people who doodle, you would know that it is rather strange state of mind to be in. The body is almost not involved in the activity of drawing and your hand is hardly lifted from the paper, where it makes rhythmical strokes and expanding lines without you consciously realizing what it is you are doing. The shapes, directions of line and their development can only be assessed when you are out of this ‘zone’. You stop doodling as soon as you realise what you are doing. The doodle is solely a result of unconscious activity and must not be confused with a sketch or a note, both of which are conscious activities.

The most common doodles are geometrical shapes, endlessly expanding and filling all the blank spaces of the available paper. The appearance and development of these drawings are unpredictable but claims that connections can be drawn with the environment you are in, with your state of mind or subconscious issues at the back of your mind seem likely to be true, at least in part.

When you doodle it feels like that in some way you are in two different worlds, inward and outward, and there is a feeling of infinity in both. The state is very similar to daydreaming, but the difference is that when doodling you are very aware of the environment around you. As soon as something in the rhythm around you changes, perhaps a sharp change in the lecturer’s voice tone or a drop in the phone signal, your doodle stops and you feel disturbed. However, you are not disconnected from the previous audible input, nor do you forget it.

Because they are produced subconsciously, you may be quite surprised by your drawings and unable to determine exactly what prompted that specific image.

Doodling is nothing new, it seems it was equally common with medieval manuscript scribes as it is with people today. There is very interesting evidence of doodles left on manuscript margins and pen trial sheets written by Medieval book specialist and Professor at the University of British Columbia School of Information Erik Kwakkel in his blog page.[1]

It is impossible not to mention the importance of subconscious drawing in surrealist art practices, particularly Automatic drawing. Surrealists used this as a method of freeing the mind from the restrictions of logical thought.[2]

They believed that increasing the speed of hand movement, action without control by the logical mind, bypassed aesthetic conventions and social inhibitions, allowing a direct transcription of unconscious thoughts and dreamlike images.

One of the other methods was to initiate the start of the drawing with a deliberately created, albeit random in form, mark (perhaps an ink blot or a colour splash) as a suggestive starting point and let the imagination take over to produce the completed work. The multitude of associations and interpretations available to the viewer was created by this approach.

A big difference between doodling and automatic drawing is the trigger. Whilst doodling starts unconsciously, automatic drawing requires a conscious act to get oneself in a state of being unaware of the hand-mind connection in the act of drawing.

Some published studies have indicated a beneficial effect of doodling on one’s cognitive abilities.

Professor Jackie Andrade[3] from The School of Psychology, University of Plymouth, did a trial in on 40 participants who were divided in two groups – one of them had a favourable setting for doodling, and the other one was denied such a possibility. The results led to the conclusion that doodling aids the ability to concentrate as well as increasing one’s recollection of things heard.

This mirrors other findings that Dual-tasking, particularly when one is a manual activity and the other is directed to audible perception, has been found to be a good precondition to avoiding the appearance of intrusive thoughts and the inability to concentrate. Doodling does not take attention away from the audible inputs but rather helps us to stay alert and focus on the present moment.

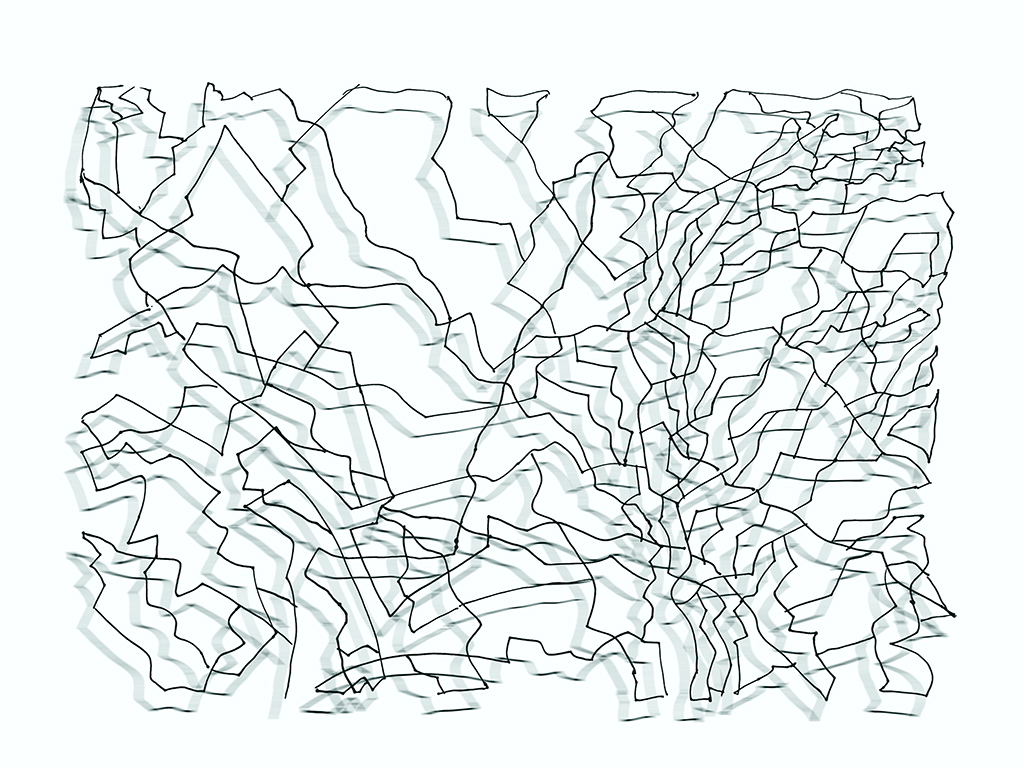

I was lucky enough never to have been prevented or stopped whilst in the process of doodling, either by my teachers at school or by some other pre-set code of conduct, but only now I fully realise the benefits of these liberties. Over the years I have made many doodles, some of which I have kept, and I am now using those unconscious images as a source of inspiration for some of my conscious drawings.

[1] Erik Kwakkel, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Continental Scribes in Rochester Cathedral Priory, 1075-1150,” in Writing in Context: Insular Manuscript Culture. Erik Kwakkel, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Book Culture (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2013), 231-61.

[2] The Automatic Message: The Magnetic Fields / The Immaculate Conception.

[3] Professor Jackie Andrade from School of Psychology, University of Plymouth, U.K. Research article What does doodling do? First published: 27 February 2009.

Coloured pencils on paper, 54 x 74 cm

Coloured marker pens on paper, 29.5 x 40.5 cm

Coloured marker pens on paper, 29.5 x 40.5 cm